|

Today my Facebook page reminded me that it was exactly one year ago when my special report, A Crime Hidden in Plain Sight: Human Trafficking in Milwaukee, was published by the Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service. At the time, I didn't really realize that that project was my first attempt at data journalism, but now after going through this MOOC and learning about the complexities of data journalism, I can see why I had such a difficult time taking on that project without any prior training in data-driven storytelling.

The free online MOOC class, "Data Exploration and Storytelling: Finding Stories in Data with Exploratory Analysis and Visualization" shed light on the different dynamics and processes that I went through last year but did not have a name for. Additionally, it provided a wealth of new knowledge, insight, tools and tips to inspire and begin to equip us with what we'll need to know to embark on our mission to attempt more serious data journalism this semester and in the future. At times it was overwhelming, but the content of the course was a great starting point that laid out different areas we can explore later on as we begin to do our own data journalism and not just watch videos about it. The course exposed the intricacies, technicalities and complexities of data journalism, but more than anything, it showed me how similar it is to tell stories about data as it is to tell stories in a more traditional way about people or events. Time and time again, the course emphasized the importance of contextualizing data and stressed the severe implications of not doing so. As with any kind of reporting, the journalist has the responsibility to craft as accurate of a narrative as possible so as to not misrepresent people or reality. It is our job to seek to communicate truth to the best of our ability. Though numbers, statistics and other forms of data might seem able to make truthful storytelling more straightforward, this MOOC illustrated how easily data can be misunderstood, misrepresented or manipulated in a way that serves neither the reader nor the public in general. This will be essential to keep in mind for the remainder of the semester as well as well into the future as we become journalists and even just informed citizens. One of my favorite takeaways from this MOOC that I will carry forward is the way that traditional, personal narrative reporting can complement and strengthen data journalism. I learned that data-driven stories can still have the powerful characters and everything that I love about storytelling, but the content of the story is just truly being driven by patterns and analyzed statistics instead of just individuals' experiences. I am inspired by ways that organizations like the Solutions Journalism Network use data to tell powerful stories that can affect positive social change, and I'm really intrigued by the potential that this form of storytelling has for our class and for all of us going forward. Check out my week by week evaluation of the MOOC HERE!

0 Comments

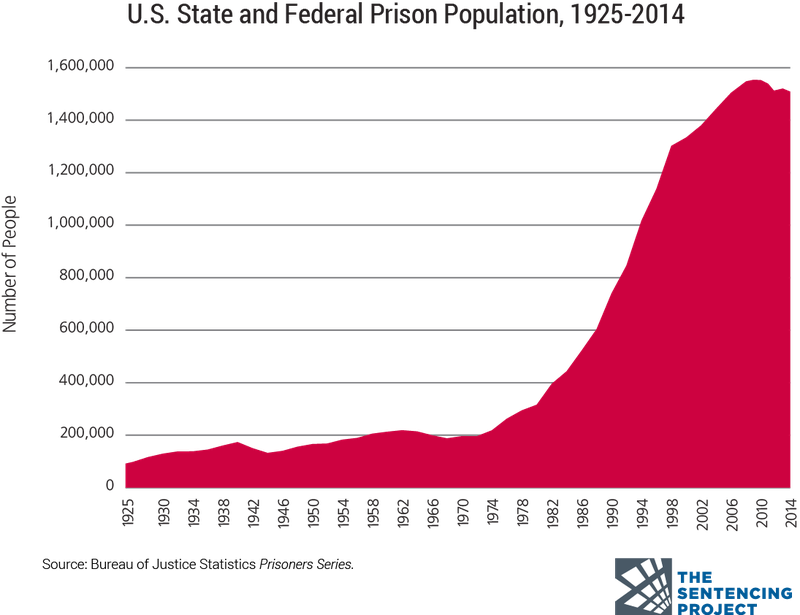

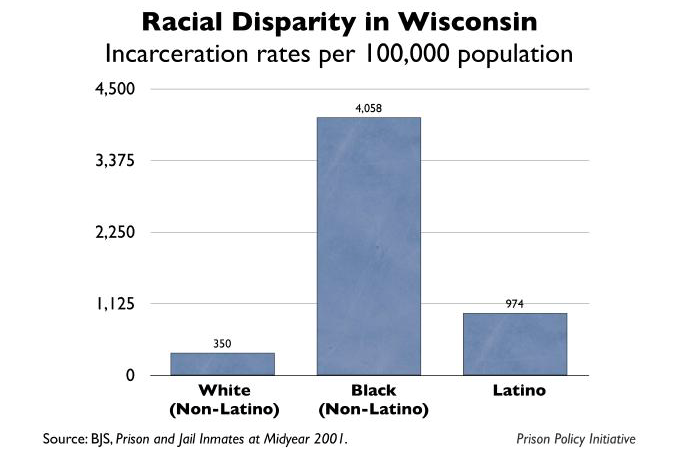

Last night I heard the renowned Black Lives Matter activist Shaun King speak at my university. As expected when listening to the message of someone you greatly admire, it was an immensely powerful experience. The message of his talk was that it is important for us to recognize the true nature of the moment we are in in history in order for us to move forward, pointing out that oftentimes humans operate under the inaccurate perception that we are constantly improving and the world around us is constantly getting incrementally better. Rather, he said, the pattern is much more fluctuating and that we have "dips" in our history. He alluded to the fact that we are on our way down into a "dip" now, and that when people ask, "What is this, the 60s?" they are ignoring the fact that we could actually be living in such strenuous times in the year 2017. His visual aids were telling and also inspiring for our ambitions of creating striking and illustrative data visualization, especially in regards to my area of research, the change in incarceration and how it has impacted people in Milwaukee depending on where they live. Wisconsin, and Milwaukee in particular, incarcerates black men at a higher rate than anywhere else in the country. This has devastating effects on families, communities, economics, and the health of our local democracy for innumerable reasons. As a jumping off point for our research, I found some information regarding how ZIP codes are disproportionately impacted by incarceration, how young people are affected by the juvenile justice system, how racial disparity manifests in incarceration, what this looks like in Wisconsin, how that affects the workforce and economic development (and this), how it impacts children, families and the community's wellbeing as a whole, and other important data around the incarceration of primarily black men in Milwaukee.

As NPR and other sources have investigated, this is one area where Milwaukee has gotten worse not better since the marches in 1967.  The Bridging Selma project created by students at Morgan State University and West Virginia University can serve as an example and inspiration to our project this year. They both seek to look at a city 50 years after its moment in the spotlight of Civil Rights history. (screen grab courtesy of Bridging Selma website) Our third class marked the third day of brainstorming for our capstone data journalism project that is to honor the 50th anniversary of the open housing marches in Milwaukee. The three hour discussion left me feeling both excited and overwhelmed, but more than anything, it made me hyperaware that our capstone class definitely has our work cut out for us. We set out to narrow down our topic, and did so to some extent. However, rather than feeling more confident in what we know, I feel that I am approaching the stage of knowing enough to more fully recognize the extent of what we DON'T know yet. This is a fun yet daunting place to dwell in.

With the help of James Brust from the Wakerly Media Lab and our guest, Joe Yeado from the Public Policy Forum, our class was able to have a productive conversation where a lot of ideas were brought up and important concerns and considerations rose to the surface. We looked at the guiding document that Wisconsin Civil Rights leader Lloyd A. Barbee wrote in 1963 to see how we could use data to show the change over time in the five areas he addressed as major civil rights obstacles in Milwaukee: human relations, political action, welfare, unemployment, and internal difficulties. Yeado offered insightful advice from his experience doing research on education in Milwaukee for how our class can obtain data, what data is already available and where we can start looking. This knowledge will undoubtedly prove crucial as we begin to attempt to take on this ambitious project. Professor Lowe also showed us several examples created by students and professional/amateur (pro-am) collaborations to inspire us and give us a better idea of what we're up against in pursuit of "a trophy." All of the projects were incredibly impressive, and there were shared commonalities among all of them that were key to their strength. Each of the projects had a clearly identifiable, straightforward central question. This allowed them to take something simple and laser-focused, and to do it really, really well. I think this is something we must keep in mind. It is much more powerful and effective to take a smaller, more manageable question and to explore it thoroughly and present it attractively rather than to bite off more than we can chew and present relatively sloppy, half-told pieces of a massive, complex story. Even the example projects that seemed to take on a broader scope had a very specific lens that allowed their work to make sense. As far as having the skills required to accomplish something as excellent as these example projects, I have nothing but confidence in us. We are more than capable of collectively producing something to the same caliber as these exceptional projects using data interactives, text, photo, video and audio, but first, we must really zero in on our central question. The extent that we reasonably set ourselves up to be successful with the project we choose to take on will be a huge determining factor in our realized success. Some questions we are tossing around right now are: What has changed in the past 50 years? What hasn't? What has prevented certain things from changing? Are Milwaukee's youth better off than young people were 50 years ago? I am nervous about us going too broad in scope and therefore losing some of the power our stories could have with a clearer focus, but believe that this clarity will hopefully come in the next couple stages of our project's development. What we cannot do is attempt to tell the entire story of the city of Milwaukee over the past 50 years, because we will fail and not serve anyone well. In order to do these important stories justice, we need to all feel on the same page and that we have a clear idea of what the stories are. We need to start to be realistic about what we're taking on and begin to think critically about all that is encompassed in each of Barbee's five points that we are hoping to explore, because they are each so dense and still not all-encompassing. For example, in the first point alone, there is a enough to explore to keep an entire class more than busy for an entire semester. The role that discrimination has played in housing and employment in the city over the years is fascinating and nuanced. The history of housing policy and anti-discrimination policy is as well. "1. Human relations. Wisconsin's problems are discrimination in employment, housing, and some public accommodations. These problems could be solved by legislation, executive action, and more vigorous private initiative." While we need to be focused, we also need to be thoughtful and careful of the perspectives we represent and exclude in the process. This will be our biggest challenge, zeroing in while not oversimplifying a complex situation too much. Since each of these five points is so broad, there is much room for our discretion, decision-making, and implicit bias. We need to be extremely conscious of how we tell these stories, and whose and what stories could be missing, in order to do our project justice. Even in all the points that the five areas touch on, there are areas that have been crucial in shaping Milwaukee over the past 50 years that were not touched on, including criminal justice, policing, mass incarceration, violence, poverty, access to opportunities and economic development. I'm not suggesting that we take on even more issues, but I just raise this point to heighten our awareness that no matter what we do, we will inherently be keeping important pieces out of the conversation, and we need to be thinking of the impact that will have when we tell our stories. I really appreciated James's point that our project's focus should not be derived from our own interpretation of Barbee's letter, but rather from our community members who live in this city and feel firsthand what has changed and what has remained stagnant. I hope we continue on this train of thought and seriously consider how we can go about this. I am curious and excited to learn about the prospects of Julie conducting some kind of survey to gain community perspective in this process. I think our goals now are to narrow our focus and select a singular guiding question, with the intention of telling a story that is driven by community members' perspectives and stories and backed up by data. We should aspire to hit that sweet spot of personal stories that appeal to readers and data that legitimizes and contextualizes those stories. As with any good meeting, I left our last class with some ideas for action items, our next steps. I think we need to start to identify potential data points we could explore and include as well as start to brainstorm specific people we could feature and build up as "characters" in telling our story. Once we begin to identify more concrete things, I think we will gain a better, more realistic idea of what is possible for us to accomplish in the next few months. 1. Human relations. Wisconsin's problems are discrimination in employment, housing, and some public accommodations. These problems could be solved by legislation, executive action, and more vigorous private initiative. Data points/relevant topics:

Potential "characters":

2. Political action. The Negro population of approximately 80,000 is small compared to the total state population. Therefore their problems appear to be undeserving of sufficient attention in the eyes of political leaders for immediate solution. Civil Rights is an issue that is inevitably "put off until later" in Wisconsin. The number of qualified Negroes registered and voting is shamefully small. Negro elected officials are few, and are lacking in patronage. Active Negro participation in both parties at all levels is negligible. Data points/relevant topics:

Potential "characters":

3. Welfare. There is a swelling wave of opposition to welfare in Wisconsin. It began with one-year residence for relief law passed by the Legislature in 1957. It is presently manifested by a bill before the legislature to jail mothers of illegitimate children. Data points/relevant topics:

Potential "characters":

4. Unemployment. Wisconsin has a high rate of Negro unemployment and a high school drop-out rate. Data points/relevant topics:

Potential "characters":

5. Internal difficulties. Although there is general acceptance of human rights, there is not enough active promotion of effective human rights programs in Wisconsin. Young, new leadership is frustrated by old and impotent nominal leaders. Established reputed liberals and currently self-styled liberals dissipate energy by excessive talking. Data points/relevant topics:

Potential "characters":

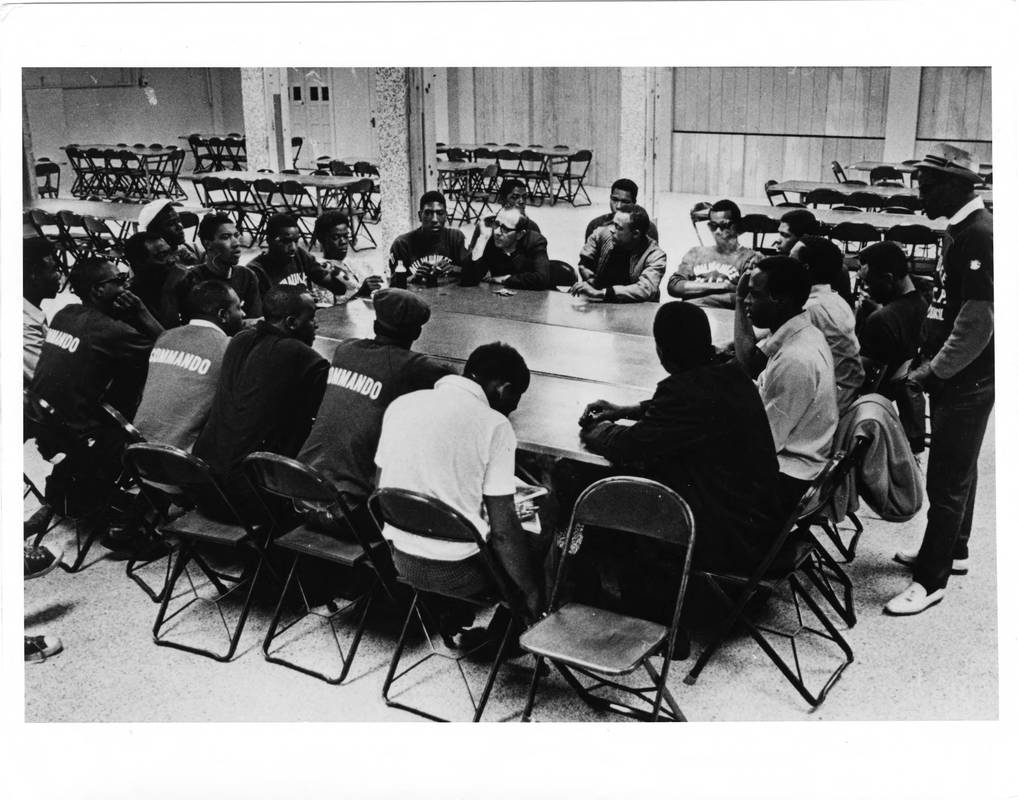

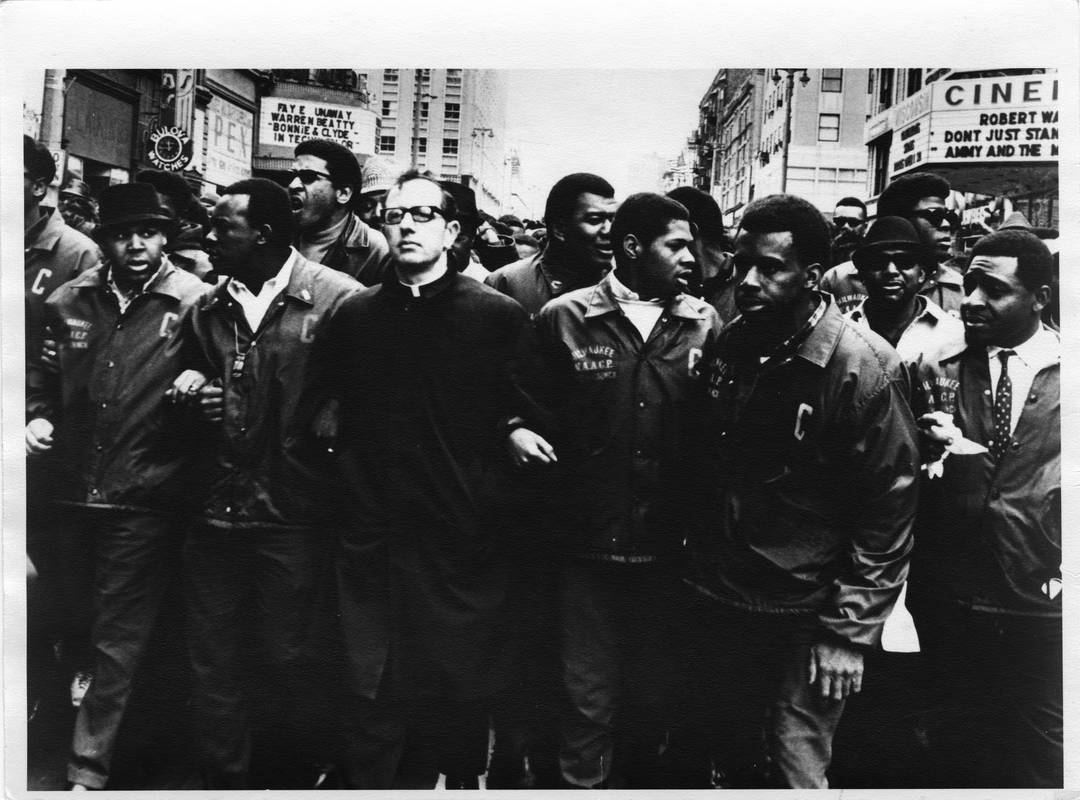

This is just a starting point to get our brains going. It is nowhere near exhaustive, and I'm sure that everyone else has a wealth of ideas as well. As a political science student, I could dig into and debate each of these topics for hours, but now it's time to crack down and do some journalism. I personally feel way in over my head, but I'm looking forward to working together with my peers to balance each other out, keep each other in check and on track, and to make this happen. I experienced the significance and importance of the Fair Housing Marches in a very real way tonight, surrounded by teenagers I love and in the presence of a living legend. Glancing back and forth between the enthralled faces of my students and the enraged but encouraging face of Prentice McKinney very clearly illustrated why these stories need to be told 50 years later. McKinney is one of the original Commandos who played a major leadership role in orchestrating the Fair Housing Marches in Milwaukee in 1967, usually with a cigarette in hand. The commandos were a militant but peaceful group of young black men who lead demonstrations and protected the marchers and spokespeople as part of Milwaukee's NAACP Youth Council.

McKinney didn't seem too excited to talk to me personally, but his face lit up when he began to speak to the young leaders in the room, pacing back and forth with his arms moving with every word. He told stories of the racism he experienced as a young person, the anger he felt, the kind of life he wanted his mother to be able to have, and the hopes he had for future generations to have a better quality of life than he did. McKinney sought to embolden the students in the room to take his torch and become the next generation of youth activists in Milwaukee. He spoke passionately about his fight and how Milwaukee used to be the most segregated city in the country. Then, one of the students spoke up and said, "It still is." McKinney nodded solemnly in knowing agreement. Though not surprising, it was so powerful to be in that room and hear about McKinney's struggle 50 years ago while also listening to a 16-year-old boy describe how he feels like a "second class citizen" in his own city in 2017. The students could be McKinney's grandchildren, and they are who he marched for. I'm telling you about this encounter because it flooded my mind with ideas we could do for our capstone project on the anniversary of the marches. Though it would be a difficult undertaking to quantify, I think it would be so fascinating to present data in a way to show if the quality of life has been improving by generation. From both empirical data and personal stories, we could compare life in Milwaukee for people of color in 1967 to 2017. Though there have been a plethora of studies done to show that there is severe racial disparity and inequality in Milwaukee, I think it would be incredibly interesting and impactful to present it in the frame of: this is what our elders fought for 50 years ago; this is is what their life was like here, and this is what it's like for black youth now. Though it may be frustrating for all involved, I think it is important to know what has changed and what hasn't, what's gotten better, and what's gotten worse. Some factors I think would be essential to look into are changes in housing policy, prominence of housing discrimination, economic investment/disinvestment by neighborhood, income inequality and income mobility. I recognize that the big question in this situation is: why is Milwaukee still the most segregated city in the country 50 years later, but I am having doubts that we would be able to tackle that in an effective way over the course of a couple months. I think that all factors of oppression are intersectional, and I am afraid of oversimplifying a complex historical issue. However, it would be worth pursuing this ambition, and I look forward to learning if any of my classmates have ideas on how we could approach a question as daunting as that. Ultimately, I think our data visualization could serve as an educational tool to community members, but especially to our youth. I think it is so important to contextualize the way things are in this city, and by displaying data over the course of generations, I think young people would have a better idea of why their lives are shaped the way they are and could feel more empowered to follow in the footsteps of those who came before, the courageous leaders like McKinney. We have so much to learn from our elders for the sake of our youth. Despite any shady "look" that Professor Lowe may or not throw at students when they walk into a classroom too close to the time that the class is intended to start, I felt nothing but good vibes as I took my seat among a rockstar group of students for our first day of our journalism capstone course.

Looking around at familiar faces and other faces that I have heard nothing but good things about, I felt optimistic about what we would be able to accomplish together over the course of the next few months. When we learned a little more about what the semester would consist of, the positive energy in the room only seemed to increase. I was thrilled to hear that we would be taking it upon ourselves, with the help of an online course, to become better at using data to tell stories in a visual and/or interactive way. No matter how each of us plans to use storytelling going forward in our lives, data visualization will only continue to play a more and more important role. The potential subject of our work was also greeted with a warm welcome. The 50th Anniversary of the Fair Housing Marches in Milwaukee is a historic landmark that is deserving of every ounce of attention it receives over the next year or so. I am fascinated by the stories of the marches and the way that housing policy has shaped this city I call home and am excited to work to make information about the significance of these events more accessible and interesting to the average Milwaukeean. Also, Fr. James Groppi is one of my absolute all time heroes, so any excuse I have to learn more about him is an always appreciated opportunity. (And yes, Professor Lowe, it will also be cool to win a trophy.) In order to embrace this challenge and to hold ourselves and each other accountable to the kind of growth we would like to see and high quality pieces we are expecting to produce in this capstone, we took an honest look at our perceived strengths and weaknesses during the first class period and discussed them with each other. Strengths:

Weaknesses:

I can't wait to see the ways that we improve and the awesome projects we will create. Straightening the collar of his sport coat and clearing his voice, he eloquently answered all of my questions about the mock trial event, acting much older than 14. After we finished and he thought I had stopped paying attention, he walked back to his group of friends and whispered, "Guys! She's from the Journal Sentinel," as his head nodded in my direction. His composure had begun to dissolve even before we had gone our separate ways, when his disposition shifted from the poise of a professional who belonged in the federal courtroom we stood in, to the giddiness of a child. "Wait, am I going to be in the paper tomorrow?" he asked with anticipation. Little did he know, we were both basically freshmen in the same boat, his first mock trial and my first solo story for the Journal Sentinel. I wasn't actually that big of a deal. Smiling big, I responded that yes, he would be able to look in the Sunday paper and see his name. That's when it hit me that I would be able to do the same thing. I just started interning with the Journal Sentinel last week. I will be working closely with the main education reporter, Annysa Johnson, and writing primarily on education issues in the city of Milwaukee and the state of Wisconsin.

In my first week, despite the fact that I couldn't find the coffee maker in the newsroom or that my boss judged me for using a gold glittery notebook, I managed to call a few people and conduct some quick interviews to help Annysa complete two stories. One was about the seclusion and restraint tactics used in schools and the other was about a local Muslim leader who lead prayer in the state assembly. I even got to tag along on a trip to Madison to sit in on an education committee hearing where representatives voted on a bill with a controversial amendment that changes the way the state's school voucher program would be funded if it passed on the floor. On Saturday, I got to cover the regional mock trial competition for Milwaukee area high school students. Talking to students about their experiences in the program and their perspectives about the issue of police use of force that they were debating put me much more in my wheelhouse than having to navigate dry newsroom humor or keep an adult-like attention span in a cubicle like I had struggled to do the week prior. Parts of the story reminded me of something I would have covered for the Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, which put me at ease, and it landed me my first solo byline for the JS, right there on page 3A of the Sunday paper. Graduating from a Wisconsin public high school and then working with high school students on Milwaukee's northwest side for the past three years has left me with plenty of passion about the state of education in this city. I am excited to learn more about the nuances and the challenges of the education system, and I can't wait to share stories of students and structures that will contribute to a fuller community conversation. Stay tuned to this blog to join in my journey. As of yet, I haven't met my Logan Huntzberger in the newsroom, and I don't quite feel qualified enough to start my dream girl band called All the President's Women with my roommates, but I'll keep you posted as I start to feel more and more like the fierce version of Rory Gilmore or the fem Woodward and Bernstein. Until then, I'll try to cling to my colleague Crocker across the cubicle's piece of advice for an aspiring journalist: 1. Pay attention and tell the truth. 2. Be kind. Final project teaches that the best journalism comes when you care, even if that makes it harder12/9/2015

If you really want to get a feel for what working on this final project was like for me, you should grab a bag of dark chocolate-covered espresso beans and head to Johnston Hall in the middle of the night. Put your headphones in, and before you begin meticulously editing the hour and a half of footage you have to get down to a three-minute story, make sure you turn on the playlist that Youtube created around the song "Honest" by Joseph. Trust me, without Spotify on those desktops, this is the only thing that will keep you sane as you embark on the biggest and toughest project of your budding journalism career.

Completing my final project for #loweclass taught me much more than I could have anticipated. I decided to look deeper into the situation of human trafficking in Milwaukee after writing several news stories about the topic over the summer and then reading the recent piece by The Guardian. As a person who is passionate about people and dignity, an issue like human trafficking really breaks my heart and overwhelms me. The project quickly took over most of my thoughts. (You can ask any of my ten roommates for verification. They all now know more about the commercial sex trade in Milwaukee than the average college student,) The more I learned about how pervasive and devastating the issue is here in our city, the more I wanted to know and the more I wanted to share. I became inundated with sources and interviews and perspectives. This is normally a journalist's dream, and it was wonderful in that sense. However having so much material to work with addressing an issue that only became more and more complex to me became quite the challenge. I struggled to stay focused and to zone in on one aspect of the story. A new challenge I faced was a strong sense of responsibility I felt to the story. The more work I did, the more invested I became in the piece and the heavier it felt. It was the coolest feeling in the world to think that what I wrote or communicated through my storytelling could influence public discourse on a topic that I truly cared about, but that added exponentially more pressure to every word I said. I wanted to best represent everything I heard, but not in an overly emotional way or in a way that favored or valued one perspective over another, because through the work I learned that this issue just like every other one does have its elements of politics. I hoped that by laying it all out there, realities would become more clear and I could encourage work toward meaningful solutions to the crazy problem I was learning about. Getting so into this story was fun in its own sense (even though some days it was deeply depressing), but it also resulted in many hours staring at a screen with only one or two sentences actually being written. As you could imagine, my written piece may be a little bit all over the place, but it is still something I am proud of. Please consider giving it a read here! I will be continuing to edit it so it can truly shine as my best piece of journalism to date, because I know there are areas that can be improved. The video aspect of my story presented a whole other set of challenges, but I think it paid off. Laura Johnson is an incredible example of someone who has been affected by trafficking in our community and is now advocating on behalf of others. I was honored to be able to elevate her story because I believe she has a message worthy of all of our attention. It also felt right that someone who had experienced what I was writing about got to tell her story herself. She deserves that agency, and I think her face, voice and conviction sends a much stronger message than my words ever could. It's safe to say that I chose her as a subject because I believed that she was a powerful storyteller, not because I thought of a ton of cool ideas for filming b-roll and different shots to enhance my video. That did pose its own challenges, because it turns out you do actually need a lot of b-roll to make a strong film. However, I think it turned out strong nonetheless! Though tedious, I genuinely feel it was a privilege to be able to dissect an hour and a half of such a fascinating and captivating interview. I hope I did justice to her testimony. Check it out above and decide for yourself! I'm kind of sad to say it, but this is my last blog post coming from #loweclass. This semester has challenged and pushed me in ways I didn't know I was capable of, and for that, I am so so thankful. Thanks for reading, and please stay tuned for more work of mine coming related to this issue of human trafficking in the Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service. Marquette students learn about social justice while I learn how to make smart phone videos11/16/2015

Kristen Hartlieb became the star of my first video the second she turned the corner toward the Alumni Memorial Union at 6:37 a.m., suitcase in tow. The sophomore student in the Marquette University College of Education had no idea what she was in for when she agreed to be the muse of an amateur filmmaker throughout her trip to the Ignatian Family Teach-in for Justice in Washington, D.C., but it turned out to be a growing experience all. A iPhone camera was pointed on Kristen or her surroundings from the moment she joined the group in the morning to the moment the plane took off. My goal was to create a video, using only my iPhone to film and Adobe Premiere Pro to edit, that would seem like Kristen was organically telling her own story of attending the teach-in without me being involved.

The process of working toward that goal ironically resulted in me being heavily involved in the storytelling process and also heavily in Kristen's face. I learned two important takeaways for future filming attempts: Make better use of the double-barreled questions. I struggled asking questions in a strategic and open way that would encourage Kristen to freely share her thoughts, insight and context to create the full story with a nut graph. This is an area of interviewing that can always be improved upon, and similar to audio stories, it is extremely noticeable and much more difficult in video to have interrupted answers from the subject. I'm so thankful that Kristen was patient with me needing to rephrase questions so the answers would flow. Shoot more footage than you think you'll need. Speaking of Kristen being patient, she never complained about me filming basically her every move. Her biggest form of rebellion was the occasional silly face in the camera, yet in the editing process I still wished I had more footage to work with. I've heard this before, and I told myself so many times throughout the weekend: film more than you think you'll need. I had plenty of footage to work with, but this process really drove the point home that you can never really have too much. Editing in Premiere was more time-consuming than anticipated, but overall pretty intuitive and fun. I have a lot of room for improvement in my video making skills, but I'm happy with how my first attempt went. I hope you enjoy it, learn a thing or two about how awesome the teach-in was and think Kristen is as adorable as I do. There are some things that you can read or hear every day of your life and still need to read or hear again tomorrow. Everyone has a story is one of those things. It may be the most popular credo among journalists, so much so that it’s bordering on cliché, but that does not make it any less true. People have latched onto this idea in recent years in exciting ways with easily accessible new forms of storytelling in digital journalism. The stories of “normal,” everyday people are being told, shared and enjoyed at an exponentially growing pace. Accounts like the vastly successful Humans of New York pop up all the time. What’s charming about this trending technique is its impact while maintaining brevity and simplicity, usually using only photos and maybe audio with short captions to communicate. Milwaukee is also embracing the concept of giving voice to ordinary individuals with extraordinary stories through outlets like the On the Block section of the Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service and Milwaukee Stories. Such platforms can provide a more nuanced backstory to someone who may appear a familiar character in city life, or they can introduce the audience to something completely new to them. The New York Times produced their own impeccable version of this type of project in 2009. “One in 8 Million” uses strong black and white photography slideshows complemented by audio interviews to illustrate a variety of 54 different New Yorkers. As #loweclass begins to embark on the journey that is learning how to produce video content, we went back to the basics to remind ourselves of our fundamental purpose as journalists. That is, doing our best to help others understand the significance of the idea that everyone has a story. We used Al Tompkin’s 10 Commandments of Video as a frame for looking at and learning from the effective storytelling in “One in 8 Million.” One of Tompkin’s commandments is “Thou shalt focus their story into three words.” The featured stories in “One in 8 Million” effectively embody this through their titles. The flattering and intriguing title each person is given like “The Teenage Mother,” “The Tolerance Teacher” and “The Uncertain Gang Member” sums up each story. The photography in this project accomplishes much of what video does. It follows Tompkin’s commandment, “Keep thy shot steady,” by capturing glances into the subjects’ lives that the audience can soak in. For example, the featured image at the top of this page creatively illustrates the new way that the subject sees herself now that she has a child. Other images in various vignettes live out Tompkin’s commandment that recommends using cutaways and sequences by focusing a portion of the photos on things other than just the subject. That same example, “The Teenage Mother,” uses some images of just the baby and other powerful cutaway shots like one of the mother holding her daughter’s hand. It utilizes sequence with several shots of mom and daughter walking outside with the stroller. “The Tolerance Teacher” uses cutaways to show other people that the subject interacts with and influences and the environment that he works in. “The Uncertain Gang Member” makes good use of sequence by demonstrating the flow of the subject’s school day and of cutaways with shots of just the subject’s tattoos. Some of the most compelling shots in these pieces are so powerful because they follow Tompkin’s commandment, “Though shalt put the camera on the shadow side of the subject.” The photographers use light and shadow to their advantage, and it is especially stark because of the black and white. One of my favorite examples of this was also in the “The Uncertain Gang Member.” The way the subject was juxtaposed between lightness and darkness with a haunting shadow cast over his face enhanced the story in an important and creative way. What stuck out to me most in all of the “One in 8 Million” pieces was how thorough the reporting was, which followed another of Tompkin’s commandments of “choosing a background that enhances the interview.” Each of the vignettes captured the subjects in different settings that make up their environment, giving the audience a more holistic, dimensional interaction with the subjects’ stories.

Reviewing the “One in 8 Million” package was a way for me to immerse myself in good storytelling, a practice I am making habitual. Pausing to be more conscious of what amazing people might be surrounding me reminds me that journalism can and does happen anywhere and everywhere. Maybe it’s not a bad thing to have the mantra of, “Everyone has a story,” branded in my mind. Without it, I never would have had the courage or conviction to approach a motorcyclist on a street corner as I waited on my bike for the light to change, I never would have learned such wisdom from my friend and I never would have known about one of my eccentric neighbors I run past. James Foley's parents visit their son's alma mater to speak as both advocates and mourners10/14/2015 The students of #loweclass weren’t too sure how to react when we found out that Diane and John Foley, James Foley’s parents, would be visiting our class in 10 minutes. We hadn’t prepared anything, but the name James Foley stirred up something in each of us. We all knew his name and something of his story. He was the Marquette alumni journalist who was captured and killed by ISIS while working to tell the stories of the conflict-stricken in the Middle East. To many on our campus and around the world, he is a hero. What would his parents be like?

Much to our relief, they showed qualities that we were all familiar with, those of caring parents who both admire and worry about their kid. “It sounds like a movie but it’s not,” John Foley said when describing his son’s life as a war correspondent. He seemed proud but also frightened just by talking about it. The closest thing that I could think of was reading Lynsey Addario’s memoir "It's What I Do" that seemed more like a page-turning thriller than a realistic account of someone’s life. Addario is a conflict photographer and detailed her experiences on the job, including being kidnapped and the struggles of having a family while doing that kind of work. “We so need passionate young journalists in conflict zones, but it’s so dangerous,” Diane Foley said with a hint of worry in her voice. She explained the importance of safety precautions and risk assessment in journalism, especially among freelancers who don’t have a news organization looking out for them. Both her and her husband have become staunch advocates for preventative safety measures for journalists. They spoke on this throughout their most recent visit to Marquette, commemorating their son's birthday a year after his death. “It’s a very tricky business,” John Foley said, warning the room of aspiring journalists in front of him. It was clear to us that their strong conviction on the matter was coming from a very personal space. They want future journalists to be safer than their son was. They don’t want other parents to have to feel how they do. They even encouraged us to pursue investigative journalism and stay stateside rather than ever working abroad. Our interaction with the Foleys was something incredibly human. We were able to experience and appreciate their perspective, one that we could relate to more than we anticipated before class started. They weren’t anything strange, foreign or distant because of what they had gone through. They thought, felt and said things that I could hear my own parents saying. Their praise of Jim and admonition about safety all seemed to come from a place of deep love. That is one of my favorite parts of journalism, getting an inside look at amazing peoples’ experiences and then realizing that we’re just normal people having a conversation. It’s a reminder that everyone we have everyday conversations with has an amazing story to share too. The Foleys seemed to agree. “Jim always said that everyone has a story that needs to be told,” John Foley said, shifting the direction of the conversation and ending our time on a more hopeful note. It was almost as if they were reminding us that despite their grief and caution for journalists going forward, they are ultimately supportive of all their son stood for. They believe in what he was doing when he was captured. They know that stories are important. |

AUTHORI am a senior studying journalism and international affairs at Marquette University. I am a Milwaukee-dweller and a storyteller passionate about exploring the intersection between community-building and communication. I'd love for you to learn alongside me! ARCHIVES

March 2017

|